Our goal as women should not be to do science as well as any man, but to do it better

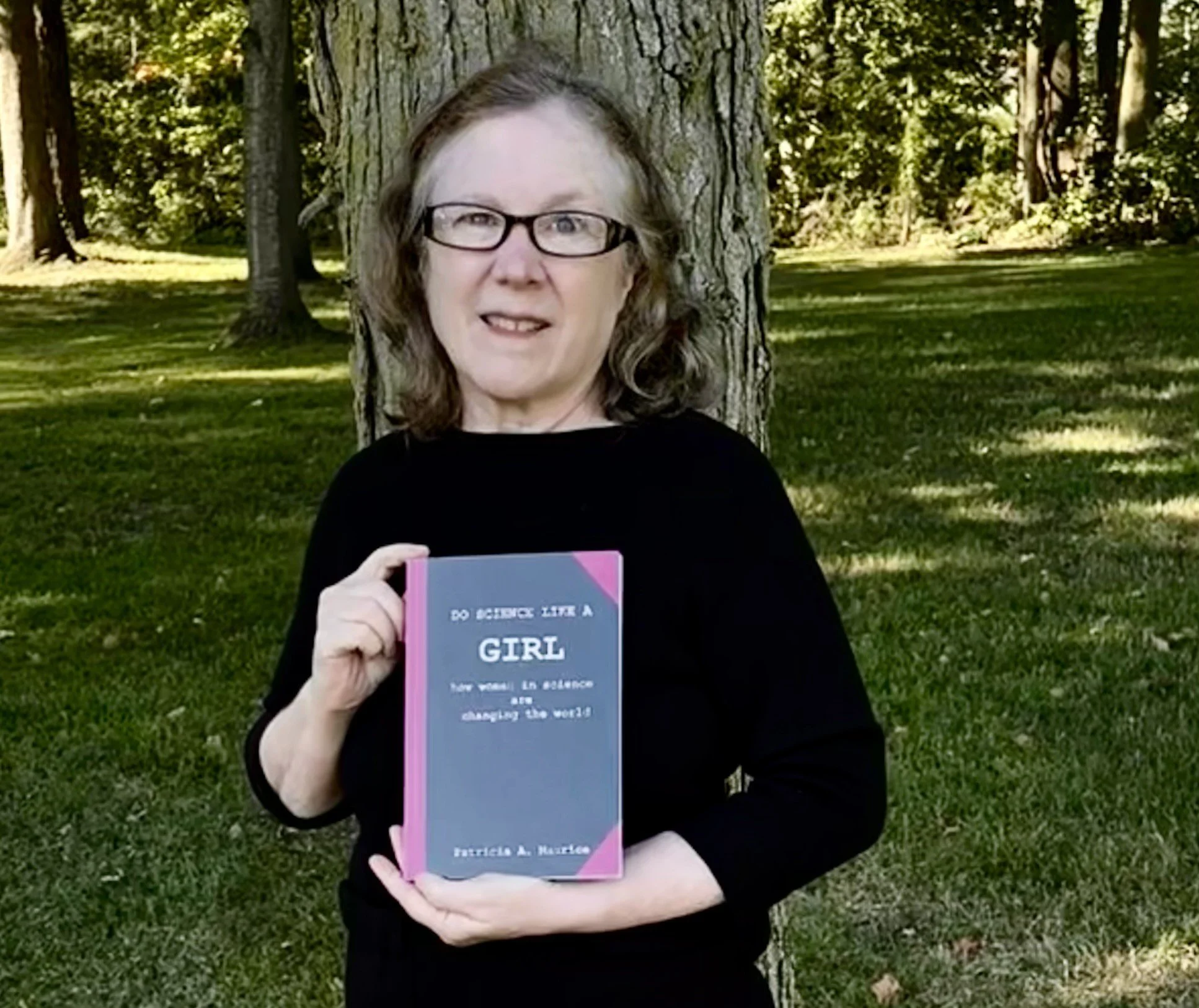

Photo credit: G. Madey

By Patricia A. Maurice

11 November 2025, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17017729

I begin Do Science Like a Girl [1] by telling my own life story in science, starting with my scientific awakening as a young girl ca. 1970, through to attaining the pinnacle of my career as a full Professor (and sometimes administrator) in a College of Engineering at a highly ranked private university in the US. I describe many exciting times of discovery along with the challenges and extra roadblocks associated with being a woman in a male-dominated field. Ultimately, I decided to step away from my career and go emeritus in my late 50s. I made my decision not because of any scandal or single incident, but because I had lost faith in a system that failed to hold accountable some of the ‘fair haired boys’ who made my life miserable on a day-to-day basis. Ultimately, I lost trust and did not want to continue to occupy a coveted academic position that someone else might be able to fill more effectively. Over the ensuing years, I have come to realize that I was not alone — that senior women are far more likely than men to leave STEMM and oftentimes due to lack of accountability and failure of trust.

The book outlines many ways women can and should work to improve the system. It details exactly why science is crucially important in the modern world and why women are needed to ensure that science is as innovative and broadly effective as possible. Individual chapters highlight women from various areas of science, engineering, and medicine who have inspired me over the years. The final chapter identifies ten ways women in STEMM are changing the world for the better, every single day.

The key messages of the book

There are three main messages. The first is to remind everyone that women have long faced additional challenges to pursuing an education and a career in STEMM, and that the problems are not all behind us. Throughout most of the developed world, the situation seemed to be getting better over the past half century. Certain fields like computer science, electrical engineering, and physics have, however, remained largely male bastions. Moreover, women continue to be under-represented at the top echelons of academia and industry. In some nations, particularly in the US, many successful women in STEMM seem to be facing a backlash. Indeed, the current US administration does not appear to understand or value science or to see any reason why women scientists are needed. This book focuses on the enormous economic and health benefits of science and discusses why a diverse scientific community is absolutely essential for science to be as broadly effective and impactful as possible.

The second message is specifically addressed to women who are professional scientists and who might be suffering some of the additional hurdles and backlash women often face. My message is simple: you are not alone. Women tend to strive for perfection and to blame themselves for extra problems they face in male-dominated fields. Impostor syndrome is real. Just knowing ‘you are not alone’ can give a woman strength and resilience to stand up for herself in the face of adversity and to not blame herself for a broken system.

Finally, women should not be content to accept the scientific community as it has been developed and defined by men. Our goal should not be to do science as well as any man — we should strive to do it better. This means we should focus on ensuring that science is more ethical, more inclusive, more innovative, more cost-effective, and ultimately more beneficial to society. We should lean into our strengths of growing up as girls to continue to transform science so that it works for everyone.

How and why I decided to write the book now

For years, I’ve considered writing a book about my life as a woman in STEMM, but I hadn’t developed a unique and compelling message. Earlier this year, I came upon several quotations by various women arguing that we do science exactly the same as men. I understand where this message comes from — there are still too many people who think women are inferior to men and that women scientists are somehow not as rigorous or innovative. So, there is a natural tendency to speak out to counter this misperception. But it occurred to me that this line of reasoning is fundamentally flawed and that this could be the topic of a unique book.

How is it flawed? First, girls are constantly being told they can’t do science because of their gender; boys don’t have to overcome the same barrier. To become a successful scientist, especially within the highest echelons of the field, a woman must be highly motivated and truly excellent. I’ve known mediocre men who succeeded, but not mediocre women. In my experience, women are often better scientists than their male colleagues at the same rank. So, we don’t do science the same way as men — we often do it better after overcoming higher barriers and hurdles.

Second, why should we accept that the status quo of science, largely developed and defined by men, is the only right way? For example, many women are especially good at interdisciplinary science, which is needed to address complex problems; but interdisciplinary strengths are often under-valued. Teaching and mentoring in science can be at least as important as research, but they are often under-valued and under-compensated. Does the race to publish always ensure the highest quality science or can it lead to short-cuts and ethical failures? Is society best served by scientists, engineers, and physicians who are primarily white (or Asian) males even though this can lead to gender gaps in data and understanding that put women and people of different ethnicities at risk? Why should we even feel a need to argue that we do science the same as men when we often do it better?

There are too many billionaire tech wizards and politicians out there, arguing that diversity is somehow a dirty word. This is the time for women to stand up and call out ‘fiddlesticks’. These men only see what they can see; they don’t perceive the enormous opportunities they are missing and the potential societal damage they are propagating.

Response to the book thus far

Even though the book is hot off the press, it has already accomplished far more than I anticipated. More than a few women colleagues have written to say that the book hit a chord. One wrote that she had been like a chick inside an egg who did not realize that the negative experiences she had encountered were widespread until the book helped her to ‘hatch’ and see the world as it is. Several have told me about their own experiences and asked for advice on how they might better navigate ongoing challenges. Many have thanked me for being so honest and open about my life, including not just my successes but my failures. I’ve heard from several men who have promised to redouble their efforts to be more proactively supportive of the women in their lives, especially in STEMM. Both women and men have thanked me for teaching them something new about the history of women in STEMM, including great women they now want to learn more about. Admittedly, at least one woman told me she never experienced any roadblocks as a woman in STEMM, although I do not think she had actually read my book at that time. That said, I’m happy for her and can only hope that such positive experiences someday become the norm. Some members of my family have been stunned to read about the difficulties I encountered — apparently, I always made my educational and career accomplishments look easy. I’m touched that several women have told me they started reading my book expecting only to read a few pages but were ‘hooked’ by my writing and ended up finishing it in only a few days. That is an incredible compliment, and I am unabashedly proud. After all, I’m a scientist not an English major. I sent my book to a few science luminaries whom I had never met and was thrilled that it fostered new friendships. That’s as good as it gets.

My hopes for longer-term impact

The book is too new to judge its longer-term impact, but I hope it will encourage more women in STEMM to write about their own experiences — both good and bad. I value trained historians, but I also think there’s a place for personal accounts and for the history of science to be viewed through the eyes of women scientists who can comment directly on how their careers have been impacted by predecessors. I hope the book will inspire girls to continue to pursue science via the stories of so many women who have accomplished great things through the ages.

Future writing projects

I love writing and am considering writing a children’s book on some aspect of women in science. Over the course of researching the book, I came up with many ideas that didn’t make it into the text but that will serve as fodder for upcoming posts for this blog. I’d love to hear suggestions from readers about what I might write in the future to help further advance the careers of women in STEMM.

How readers can contact me if they have questions or want to discuss the book with me

Readers can contact me at my professional email address at the University of Notre Dame, pmaurice@nd.edu.

How to get a copy of the book

The book is available in paperback through worldwide, on-demand printer LULU.com [2] and as an ebook at Amazon.com [3]. At Amazon, it will be available for free download from within the US on the following dates in 2025: November 11, 12, and 16. Unfortunately, Amazon cannot provide free download dates outside the country of publication at this time. If you are having trouble accessing the book, please email me and I will do what I can to help. I didn’t write this book to make royalties but to help women and girls in STEMM.

Concluding comments and questions for further thought

The observant reader will notice many references in my book to posts in this blog series [4], which I co-write and edit with my friend and colleague Janet Hering. Many of the women profiled in our blog series also appear in my book. I am glad to have been able to use the book to bring together themes from various blog posts and I hope that the book will inspire readers to go back to some of the original posts.

My questions for our readers are:

· What motivated you to become a scientist and how did you sustain your enthusiasm for science over the course of your life and career?

· Have you observed any differences in how women and men do science?

· What do you know now about science that you wish you had known when you were a girl?

References and notes

[1] Patricia A. Maurice, 2025. Do Science Like a Girl: how women in science are changing the world. M&M Honey Farms Press, Edwardsburg MI, USA, ISBN 9781300277453

[3] https://www.amazon.com/Do-Science-Like-Girl-changing-ebook/dp/B0FN6G1XRF/