Successful academic meetings: Part 1, Preparation

The calendars of senior academic leaders in STEMM are full of meetings. But a successful meeting requires careful preparation. This first part of a 3-part blog on organizing and chairing meetings gives advice on meeting preparation.

By Patricia A. Maurice

17 October 2023, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8427741

University faculty, especially senior leaders, can sometimes feel like every moment is so jam-packed that it’s hard to spend time thinking and being creative. Meetings are huge time consumers, yet academics rarely receive any training on how to plan for and lead a meeting successfully. In this first part of a three-part blog, we provide some tips for preparing for an academic meeting. Part 2 will focus on chairing a successful meeting and Part 3 on video conferencing and hybrid meetings.

Our overall goal is to offer insights from years of preparing for, chairing and attending a host of different types of academic meetings. We focus on relatively small group meetings; although, many of the tips are applicable to one-on-one or large meetings as well. While much has already been written about meetings, especially in the business world, our focus is specifically on academic meetings in STEMM chaired by a senior woman leader. This template may be helpful in preparing for and chairing a successful meeting.

Is the meeting necessary?

In planning a meeting, start by asking whether it is necessary. Unnecessary meetings waste time. Many items of information can be shared, and decisions made, over email. But, for some tasks, such as strategic planning, faculty hiring and tenure/promotion decisions, in-person (or remote) meetings are usually required. Avoid unnecessary meetings, but if a meeting must happen, keep it as short and well organized as possible. Your colleagues will thank you for it.

Are the right people invited to the meeting?

The list of invitees for some meetings, such as department chairs or deans, academic council, faculty senate, etc., is defined by academic regulations. If you are a dean, for example, and are concerned about whether your department chairs and associate deans can meet effectively, then you should consider whether some might need to be replaced. People who are overly combative or loquacious can make it difficult to hold an effective meeting.

For many meetings, you will be able to define the list of invitees/attendees. Consider whom to invite carefully: a meeting with more than ~10 attendees can become unwieldy. Leaving out ‘the wrong person’ can lead to hard feelings or make the meeting ineffective. If the same effective people are called on repeatedly, they will become oversubscribed and eventually ineffective.

Ask yourself: Who really needs to be at the meeting? Can an attendee send a substitute to help spread the workload around? Are the meeting attendee demographics inclusive?

One problem person (e.g., who drones on endlessly) can ruin a meeting; two problem people can lead to chaos. If they need to be there, it might be necessary to spend some advance leadership time to set boundaries and expectations.

Know who will be attending and their roles

A senior leader who will be chairing a meeting is responsible for knowing who will be attending and why each person is important to meeting goals. Do some advance research, especially if the attendees were invited by an assistant or colleague. I will give two examples of meetings that went wrong because of lack of preparation by the meeting leader/chair.

As an assistant professor, I was reasonably successful at bringing in a number of interdisciplinary collaborative grants. As a result, I was invited by a chair to meet with his (all male) faculty to kick-start potential collaborations. When I arrived at the meeting, I was the only woman and was ignored by the men. When the chair arrived, he spent several minutes summarizing my background and accomplishments and stressing why I was worth talking to. He never acknowledged my presence and clearly did not recognize me since he left to find out why I was ‘running late’. At this point, I was asked to go make coffee. The meeting was thankfully short. Even back in the ‘90s, the chair could have found my photo online or at least realized that I was a youngish woman. Better yet, he could have met with me one-on-one in advance.

Years later, as a center director, I was invited to a meeting with a high-level university administrator and a group of male colleagues. I was obviously mistaken for another senior woman, who had not been invited to the meeting, resulting in a good deal of confusion. It made for an uncomfortable meeting, especially since some of my male colleagues obviously found the situation hilarious.

In both instances, the primary meeting objectives were not fulfilled at least in part because the meeting chairs had not adequately prepared (and did not start the meeting with introductions).

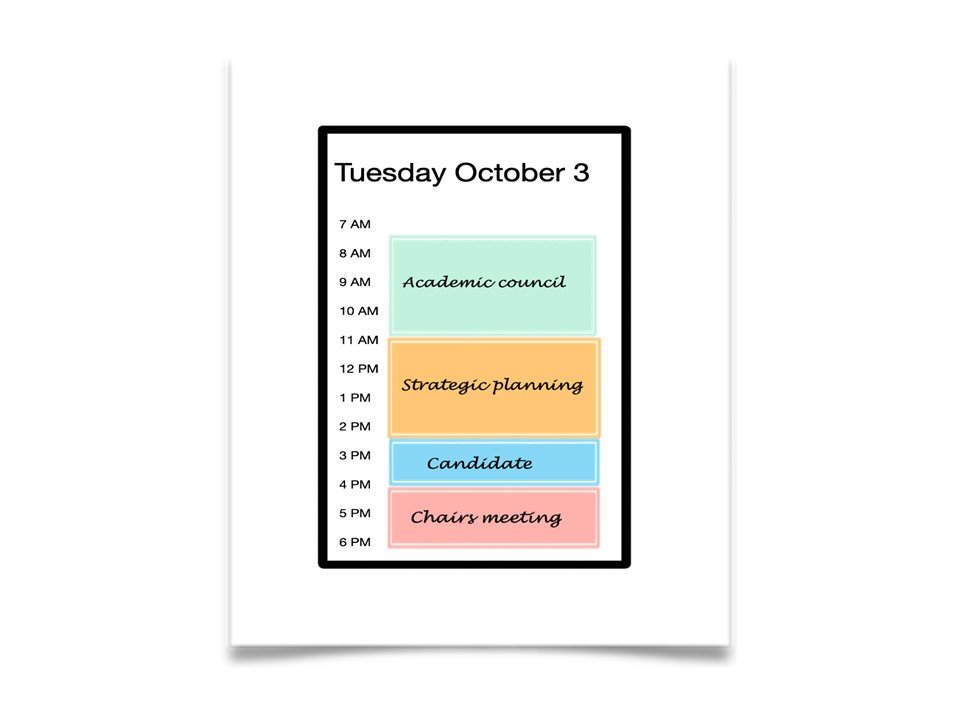

Meeting schedule/timing

Meetings should be scheduled at a time that is convenient to most attendees, taking into consideration that some faculty need to drop off/pick up children from childcare or school. I once had a male department chair schedule an important meeting at the last minute, in the evening, apparently in hopes that a few faculty members with young children (who happened to be unlikely to vote the way he wanted) would be unable to attend. This approach backfired and continued to have negative ramifications for years.

Try to be aware of or at least sensitive to major events that might conflict. For example, scheduling an important meeting just before a campus-wide festival or holiday can cause unnecessary stress. For interdisciplinary meetings, it can be hard to avoid conflicts with all major disciplinary conferences, but good advance communication is helpful. Try to ensure that the same people/disciplines are not always excluded because of schedule conflicts. For example, 3 PM might be impossible for faculty who are required to teach lengthy afternoon laboratory sections. It’s not helpful to schedule a meeting with the Chemistry department during the main annual (inter)national Chemistry conference; this can be avoided with good communication.

Allow extra time for a meeting that has multiple presentations and that involves significant use of technology.

Always strive to provide as much advance notice of a meeting as possible, and issue a schedule for standing meetings at the start of each semester. Online polls can be useful for scheduling meetings but not everyone uses them or adds results to calendars. Send out a meeting reminder a day or two before the meeting.

Make sure that the meeting is blocked off on your calendar and that you will be not be interrupted during the meeting except for emergencies.

Be sure there is enough time between meetings to allow for transit between rooms and for bio breaks. I am an advocate for university calendars that allow explicitly for scheduling time between back-to-back meetings.

Meeting agenda

Circulate a succinct meeting agenda with time intervals in advance, and invite colleagues to suggest agenda items if appropriate.

The agenda should include a short descriptive title of the meeting and the exact meeting time and location.

Before drafting the detailed agenda, clearly identify meeting goals. A meeting agenda should be focused on achieving the goals of the meeting and cover topic(s) relevant to the attendees. A well-constructed agenda can help promote attendance, foster engagement, and ensure that the meeting is productive and ends on time.

Many scientific words are taken to have different meanings depending upon the (sub)discipline; moreover, each discipline has its endemic jargon. Try to avoid jargon in the meeting title and agenda for interdisciplinary meetings and always define acronyms. For example, ACS can stand for American Chemical Society, American College of Surgeons, American Cancer Society, Animal Care Services, etc.

For lengthy meetings, bio breaks (for food, beverages, restrooms) should be included with specific times.

While setting up the meeting agenda, you can start filling in the meeting template that is provided in the link, below. The template can be used during the meeting to help in organization and reporting.

Make materials available in advance

Be sure attendees know the purpose of the meeting. If possible, make reading materials and slides readily available in advance, with key items abstracted or highlighted because everyone’s reading time is limited. Cloud/box accounts can be useful depositories for meeting materials, including post-meeting notes and summaries but watch their security and make sure everyone understands how to access and use them properly. Also, be careful that the materials aren’t lost when administrations, webmasters, etc. change. Some materials may be too sensitive for online dissemination (and even paper copies might need to be collected and shredded).

If technology will be used during the meeting, make sure that everyone knows the technical requirements (e.g., for presentations). Just because the meeting involves scientists and engineers doesn’t ensure they’ll know how to use the equipment. It can often be helpful to suggest that presenters have a back-up plan for technical failures. As an example, a taped presentation can serve as backup if a real-time demo fails.

If an important decision/vote needs to be made, it can often be helpful to hold individual or subgroup meetings in advance to gauge and drum up support, as long as it’s done in a consistent and equitable way. As the only senior woman in many situations, I was discouraged when senior men held pre-meetings that excluded me so they could come to consensus before any formal meeting that included me in the discussion. This made me feel like my ‘diverse’ opinion, as the only woman, was not valued. Exclusionary practices can turn a potential advocate into an adversary and preclude the potential benefits of diverse opinions.

The meeting room

Make sure the meeting room is of appropriate size; too small and not everyone can sit comfortably while too large and people might be too spread out to communicate effectively.

Before the meeting, ensure that any devices that might be needed are available (e.g., pointers, projectors, video screens, microphones) and in good working order. It’s always useful to have a white or black board available and readily visible by all attendees. Know how to set room lighting and open/close windows and shades. Try to ensure in advance that the meeting room is at a comfortable temperature. Many of these items can be taken care of by an assistant, if one is available.

Whenever an academic takes on a new leadership position, whether as a center director, department chair or associate dean or a higher level position such as dean, institute director, vice president, or provost, it’s important to evaluate executive meeting and conference facilities. A large budget can allow for purchase of ergonomic adjustable chairs, sophisticated videoconferencing equipment, etc. Even a tiny budget might cover some power strips to accommodate multiple laptops or installation of a mini-refrigerator or a coffee maker, or purchase of just a couple of folding chairs. I’ve been in many meetings that could have been less frustrating and more productive if a little time and money had been expended to make the meeting room reasonably comfortable and functional.

Food and bio breaks

Early morning meetings can often benefit from having coffee, tea, water and/or juice readily available, ordered in advance. If a meeting must be held over the lunch hours, be sure attendees know whether to bring their own lunches. Funds permitting, order in boxed lunches (allow attendees to pre-order based on dietary needs) and have water available, at a minimum. It’s useful to add a line to any meeting invitation asking about food allergies/sensitivities as some people can have severe allergic reactions to foods like peanuts or cinnamon (even cinnamon-flavored chewing gum). Women, even in senior leadership roles, are often expected to lay out food and clean up after a meal so make sure an assistant is scheduled to do these honors or let everyone know to clean up after themselves.

Young people are often hungry, and most academics know that a good way to assure attendance is by offering food. Make sure food preferences and sensitivities are considered in advance. For example, lactose intolerant or vegan students can feel awkward and uncomfortable in a room full of pepperoni cheese pizzas and ice cream.

Schedule time for bio breaks during lengthy meetings and be sure that attendees know the locations of the nearest restrooms and water fountains.

Questions for further consideration

· Are the next few meetings on your calendar necessary? If not, how can the tasks be accomplished without the meeting? As a senior leader, ask yourself this question at least once a week, looking forward several weeks on the calendar.

· What preconceived notions do you have that might affect how you greet a colleague? Even senior women can mistake other female faculty for students or administrative assistants.

· What meeting scheduling and calendar tools are available at your university and how well do they work? Are university personnel familiar with how to use them effectively?