An introduction to power for women in STEMM academic leadership

Understanding power and its dynamics in STEMM academics can help women leaders to avoid being subjected to abuses of power and to exercise our own power ethically, responsibly, and for the benefit of all.

By Janet G. Hering and Patricia A. Maurice

14 October 2025, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.16892592

We often avoid thinking about power in academic institutions for two main reasons. One is the association of power with coercion and corruption (or in the famous words of Lord Acton “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely” [1]). The other is our belief in academia as a meritocracy, in which our contributions and talents should be recognized and result in professional advancement without relying on power or influence.

But ignoring power and its dynamics in STEMM institutions does not make it go away. Such lack of awareness just makes it more likely that we may be subject to abuses of power by others and less likely to exercise our own power effectively and appropriately. In political science, power is the ability to influence or direct the actions, beliefs, or conduct of others. As Jeffrey Pfeffer writes, power is “foundational to success at work” [2]; power enables us to get things done and we need to understand its dynamics to wield it effectively. This is not to say that we need to accept how power is conventionally structured and wielded in academia. Academic hierarchies too often lead to misuse and abuse of power (e.g., bullying, mobbing, abusive supervision, harassment, and discrimination) [3]. Various organizations are working to combat such abuses and to support targets of abuse [4]. Often targets are members of under-represented or vulnerable groups (e.g., international students), which makes them less likely to be able to resist abuse. In addition, compelling visions for change have been presented though initiatives and in books and articles.

Types of power and how they are exercised

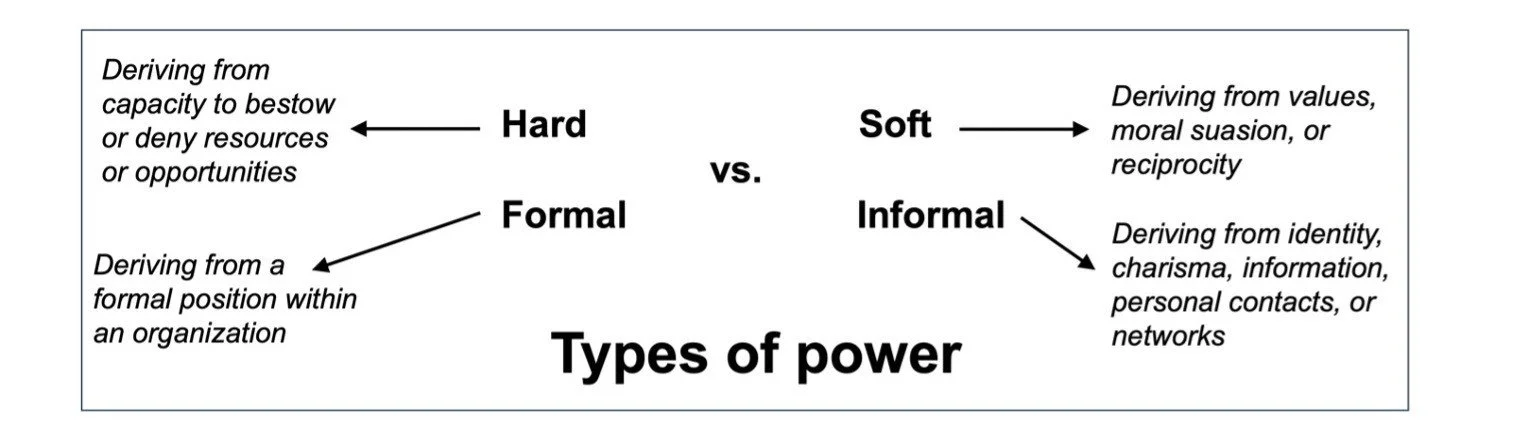

In institutions, formal power is derived from a position such as department chair, dean, provost, or president while informal power does not depend on a (current) position but rather derives from identity, charisma, contacts, and networks. Of course, these bases for informal power may also contribute to the power of an individual holding a formal position. Furthermore, individuals who have left a formal position often retain networks and access to information that contribute to their subsequent informal power. Since individuals in formal positions of power are often able to allocate (or deny access to) resources and opportunities, they are more able to wield hard power. In academic settings (which are expected to be collegial), the efficacy of hard power may be compromised by the resentment it can generate. Thus, soft power cannot be ignored even by those in positions of formal power, and it is even more important for the exercise of informal power.

Any time an academic moves to a new institution or takes on a new position, it is important to investigate and understand the formal and informal power structures [5]. This is especially crucial when moving from a public to a private institution (or vice versa) or from one nation to another. Money is a key element of power, so an understanding of budgetary processes and who holds which purse strings is essential. It is also important to understand power dynamics associated with grant funding. For example, a senior person who brings in a large amount of research funding may be granted additional power within an institution. Conversely, a junior person may be pressured to share or cede resources to more senior faculty. Good mentors and allies can provide insight on both formal and informal power structures and how to navigate them successfully.

Of course, we always hope that power will be exercised for beneficial ends and with high ethical standards, that is with fairness and equity and with respect for all individuals affected (including those indirectly affected). Some of our previous posts, however, have dealt with dishonest colleagues [6] and the need to promote ethical behavior actively [7]. We would be foolish to assume that power will always be exercised ethically in STEMM academics. Such assumptions will only make us more vulnerable to the abuse of power by others and, perhaps also, less aware of our own potential misuses of power. We should also be aware that some trade-offs (e.g., between transparent communication and privacy or confidentiality) mean that ethical behavior will be, to some extent, context dependent.

Power abuses in academia

Misuse and abuse of power in STEMM academics cannot be separated from the norms, incentives, and hierarchical structures of academia [3]. Hyper-competitiveness is common among scholars, especially in rapidly developing fields, and conventions of publishers and funding agencies tend to focus attention on a single individual as senior author or principal investigator. The ‘Matthew effect’ – “For to all those who have, more will be given” (Matthew 25:29) – has been used to characterize the continuing accumulation of renown, recognition, and resources by prominent researchers [8]. The reputation of an institution is inextricably linked with the recognition and professional stature of its leading scholars, and many institutions rely on external research grant funding brought in by scholars; together, this can create disincentives for institutions to take allegations of abuse seriously. Even individuals who experience abuse of power may feel too dependent on the perpetrators of the abuse to challenge their abusers [9, 10]. During studies or doctoral and post-doctoral training, early career researchers (ECRs) are often dependent on their supervisors for access to facilities or other resources and even continuing employment (which may have visa implications for international trainees). The tradition of personal recommendations makes ECRs highly dependent on their supervisors, a dependency that can persist well into the more junior colleagues own independent career. Evaluations by one’s professional colleagues is an ongoing element of academic careers; such evaluations can be subject to bias and unfair preferences as described in a previous post on favoritism [11].

Professors, especially women or members of under-represented groups, can also be subject to abuse of power in the form of ‘upward bullying’. This term refers to bullying behavior (sometimes called ‘mobbing’ in Europe) that is directed by students, doctoral students or postdocs against a professor (often their supervisor). Such behavior may be incited or encouraged by faculty colleagues or even academic leadership as a means of attacking the targeted professor, as we described in our post on an incident of career destruction [12]. Some key aspects of mobbing – including the often-ignored need for objective evidence, the motivating role of envy, the prevalence of social contagion, and the devastation of the process itself regardless of outcome – have been recently described by Kenneth Westhues, a leading scholar on this topic [13]. Too often, it seems that when a complaint is made against a supervisor or an administrator who is a woman (and/or a person of color), the complaint is used as an excuse to remove her rather than to resolve conflicts through communication, education, and mediation.

Working for change

Issues of power abuse in academia are increasingly being exposed [14]. High profile cases can attract mainstream media attention, but the systemic aspects of such cases often go unmentioned. Independent organizations [4] thus play a critical role, not only in supporting targets of abuse but also in calling on academic institutions to address trends and systemic deficits rather than focusing on individual ‘bad apples’.

In late 2024, a number of independent organizations in Switzerland issued a petition [15] calling on a leading Swiss technical university to take the following steps to help prevent abuses of power: (1) following up decisively on reports of mobbing, bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination with investigations and disciplinary actions; (2) issuing a public annual summary of incidents of mobbing, bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination reported to internal and external agencies that includes reporting of the proportionate actions taken by the executive board; (3) implementing an anonymous and external reporting tool for incidents concerning mobbing, bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination under the whistleblower protection act; (4) establishing a legal fund to cover complainants’ legal costs as well as public disclosure of funds expended by the institution in legal processes related to mobbing, bullying, discrimination, and sexual harassment; (5) publicly disclosing the time to doctoral degree completion, rates of successful degree completion at an appropriate level of disaggregation as well as annual reporting on reasons for departures of Ph.D. students, academic staff and (female) assistant professors; and (6) that institutional leadership takes on a personal and prominent role to send a clear message to perpetrators that such behavior is not condoned and will have consequences. Despite ongoing discussions, implementation of most of these measures is still pending. An anonymous reporting system (as requested in the petition) was launched at the beginning of October this year [16].

A vision for the future

Ending power abuse in higher education and research institutions (HERIs) is only one aspect of the many calls for their transformation for the benefit for all. The 2024 book Higher Expectations: How to Survive Academia, Make it Better for Others, and Transform the University [17], which was described by its co-authors in a guest post [18], outlines measures that individuals can take directly to improve conditions in their institutions, including breaking down hierarchies and sharing power. In her recent book, Labwork to Leadership [19], Jan Heemstra addresses power imbalances and how they can be offset within research groups and in dealing with senior colleagues. In addition to enabling power abuse, current academic incentives and norms also hinder the capacity of HERIs to engage in actionable research needed for the solution of pressing societal challenges [20]. As senior women leaders, we have deep insight into the workings of the academic system and often personal experience of its shortcomings. We are well positioned to work with ECRs [21] and male allies [22] to bring about much-needed transformation.

Concluding thoughts and questions for further discussion

Power is a complex topic. This post can only scratch the surface of how power is exercised – for good or ill – in HERIs. As senior women leaders, we could play a role in determining how this could change in the future. We would like to encourage senior women leaders to help other women succeed by sharing their insights on formal and informal power structures and their experiences in achieving and exercising power. It is only by sharing our stories that we will be able to find our collective voice and build our collective strength.

We encourage our readers to engage with us on this topic. We can be reached by email at: epistimiblog@gmail.com.

In closing, here are a few questions to stimulate further thought and discussion:

· How comfortable (or uncomfortable) are you with the exercise of power in academic institutions?

· Have you experienced or observed abuses of power in academia? If so, what was your response?

· Do you have ideas for promoting the ethical exercise of power in HERIs? Let us know!

Notes, links, and references

[1] Lord Acton Quote Archive, https://www.acton.org/research/lord-acton-quote-archive.

[2] Pfeffer, J. (2024) Learning Corner with Jeffrey Pfeffer: Get Out of Your Own Way on Your Path to Power, https://www.cornerstoneondemand.com/resources/article/learning-corner-jeffrey-pfeffer-get-out-your-own-way-your-path-power/

[3] Bössel-Debbert et al. (2025) An analysis of functional relationships between systemic conditions and unethical behavior in German academia, submitted to Meta-Psychology, https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/xj2m6_v1

[4] Academic Parity Movement, https://paritymovement.org/; Network against Abuse of Power in Science, https://www.netzwerk-mawi.de/en/; Speak Up! in Academia, https://www.speakupinacademia.ch/.

[6] https://www.epistimi.org/blog/liar-liar-campus-on-fire-how-to-cope-with-dishonest-colleagues

[7] https://www.epistimi.org/blog/why-stemm-leaders-need-to-talk-seriously-about-ethics

[8] Perc, M. (2014) “The Matthew effect in empirical data”, J. R. Soc. Interface, 1120140378, http://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0378

[9] Corbett, E., Barnett, J., Yeomans, L. and Blackwood, L. (2024) “That’s just the way it is”: bullying and harassment in STEM academia. Intl. J. STEM Ed. 11: 27, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-024-00486-3

[10] Moss, S. and Mahmoudi, M. (2021) STEM the bullying: An empirical investigation of abusive supervision in academic science, eClinicalMedicine, 40: 101121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101121

[11] https://www.epistimi.org/blog/the-dangers-of-favoritism-in-stemm-academics

[13] Westhues, K. (2025). Top Twenty Takeaways from Research on Workplace Mobbing. Journal of Workplace Mobbing, 1(1). Retrieved from https://journalofworkplacemobbing.org/index.php/jwm/article/view/403 (Accessed August 18, 2025)

[14] Täuber, S., Oliveri, N.F., Kostakopoulou, D. and Mahmoudi, M. (2022), Breaking the silence around academic harassment. FEBS Lett, 596: 2337-2344. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.14473

[15] https://www.change.org/p/weareshocked-it-is-our-collective-responsibility-to-hold-eth-zürich-accountable (The petition is still open for signatures, which can be anonymous.)

[16] “Anonymous notice on inappropriate behaviour” https://ethz.vispato.com/ (Accessed October 2, 2025)

[17] Hawkins, R. and Kern, L. (2024) Higher Expectations: How to Survive Academia, Make it Better for Others, and Transform the University, Toronto: Between the Lines, 267 pp.

[19] Heemstra, J. (2025) Labwork to Leadership: A Concise Guide to Thriving in the Science Job You Weren’t Trained For, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 315 pp.

[20] Urai, A.E. and Kelly, C. (2023) “Rethinking academia in a time of climate crisis”, eLife, 12:e84991. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.84991

[21] Hering, J.G., Green, S.A., Heckmann, L., Katehi, L.P.B, Maurice, P.A. and Young, S. (2022) “A call for an alliance between female academic leaders and early career researchers to improve the academic STEM system”, Elephant in the Lab, doi:10.5281/zenodo.6514731, https://elephantinthelab.org/a-call-for-an-alliance-between-female-academic-leaders-and-early-career-researchers-to-improve-the-academic-stem-system/