Service activities in academia need to be properly valued and supported

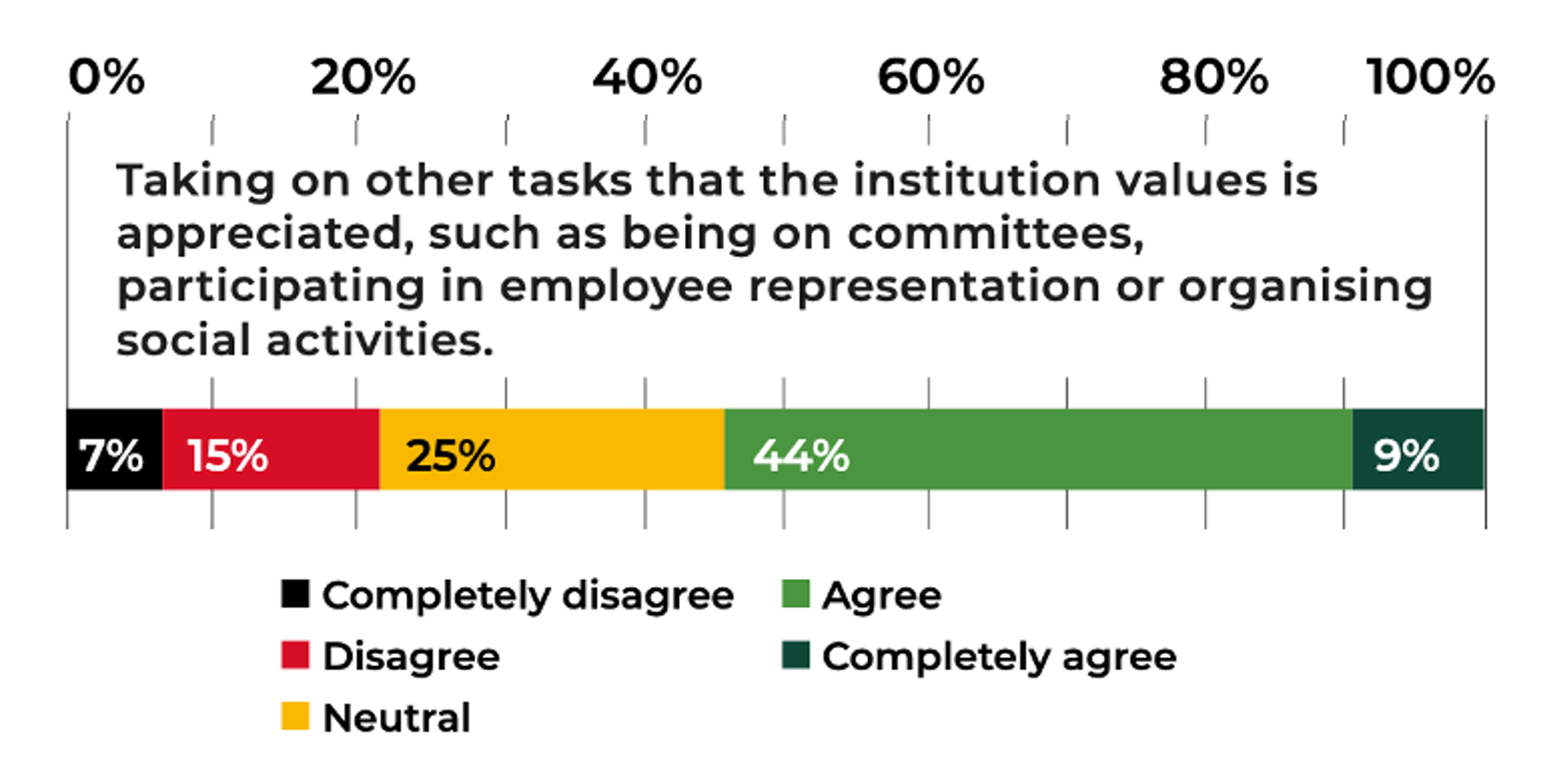

Agreement of respondents in the Dutch Recognition & Rewards Culture survey [1]

In US and UK universities, the job responsibilities of most professors are often grouped into three categories — teaching, research, and service. In European universities, service is often less explicitly recognized despite its crucial importance for institutions. Regrettably, service can become a ‘trap’ for women at all levels. We provide suggestions on how to value and manage service activities, so they serve the university and society without hijacking an academic career.

By Patricia A. Maurice and Janet G. Hering

3 February 2026, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.18386147

At typical higher education and research institutions (HERIs) in the US, faculty are evaluated based on three criteria: teaching, research, and service. Medical schools include an explicit clinical component, which can be combined with or largely supplant the research component. Research productivity is generally considered the most important criterion by far, followed by teaching, with service often considered a distant third. The preeminence of research derives from the fact that research can generate considerable external income for a university and research productivity in terms of grant awards and publications are heavily weighted in university rankings. Faculty members who acquire large research awards are ‘bankable’, and this can increase their power within an academic environment.

Academic service within an HERI can take many forms, from academic advising of students and postdocs to serving on short-term or standing committees to mentoring junior faculty or simply taking time to ensure good communication and a collegial environment. There are also many service opportunities in the broader community, such as reviewing papers and proposals, serving on professional and/or government committees and panels, and communicating with the public. Service is important to the proper functioning of any HERI and central to the role of STEMM in society. Despite this, service often falls under the category of ‘non-promotable tasks’, which are rarely given the value and attention that they deserve [2].

Academic housework as a barrier to women’s progress in academia

Many studies have shown that women in academics, including but not limited to STEMM fields, are often called upon to perform more service than their male counterparts. Macfarlane and Burg (2019) [3] conducted interviews with female and a smaller number of male professors (rank equivalent to ‘full professor’ in the US) in both STEM and non-STEM academic positions in the UK. On the basis of these interviews and the literature, they suggested that “One of the barriers to progression for women within higher education is captured by the phrase ‘academic housework’” which “refers to women taking on gendered responsibilities associated with caring in the workplace that can result in an excessive amount of time-consuming and lowly esteemed service work inhibiting, or at least delaying, their promotion chances.” The authors argue that ‘academic housework’ can represent a ‘trap’ endangering an academic woman’s career. This effect can be particularly pernicious in STEM fields where women expressed an additional sense of ‘responsibility’ to fulfil service commitments as a role model. The authors concluded that, “Both female and male professors understand their role principally in terms of research leadership, but women are more likely to emphasize the importance of academic citizenship, especially mentoring, compared to their male counterparts, an obligation that weighs especially heavily on women working in [STEM] areas”. Although the sample size was too small for the authors to examine race and ethnicity, we suspect that the intersection of race and gender would further handicap women of color in the academic workplace.

Why do women often spend more time on service?

In many instances, women may find themselves doing more committee work because of the paucity of women faculty at any rank in many disciplines, and in almost all disciplines at the highest levels of full professor, center director, chair, or dean. But societal expectations and socialization can also play a role. As the UK interviews [3] indicate, many women may simply value good ‘academic citizenship’ more than their male colleagues.

Interviews were conducted with male and female associate and full professors in the fields of economics, political science and sociology at three Danish universities in 2024 [4, 5]. This study suggested that male academics tend to be more focused on activities that directly benefit their careers, particularly research. Some men were described as ‘brazen’ in safeguarding their priorities, for example choosing to ignore emails with requests for service work or even deliberately acting in an ‘exaggerated disorganized manner’ so that they would not be expected to perform more service.

In a study conducted with faculty from 13 US universities, time diaries kept by male and female Associate and Full Professors from both STEM and non-STEM disciplines were analyzed [6]. The results indicated that women faculty spend more time on “campus service, student advising, and teaching-related activities,” whereas men spend more time on research. The study authors also found that “women received more new work requests than men and that men and women received different kinds of work requests,” leading to gendered differences in how much time could be spent on research versus teaching or service.

No matter why women spend more time on service, it does impact their careers. That said, service work is important and it needs to be valued. Whether public or private, all universities rely on funding from governmental programs and/or from donors and benefactors. If faculty do not demonstrate a devotion to excellent teaching and service to the community, we risk losing this support and thereby put our entire universities at risk.

How to address the problem of undervalued service as a barrier to the advancement of women in STEM academics

Steps can be taken to address this problem at multiple levels. As senior women in STEM, we can make some progress as individuals. Other changes will need support and engagement at the highest level of the institution.

As individuals, we can serve as role models and (informal) mentors for our junior colleagues, helping them to understand the importance of service for our universities and how best to allocate the time they spend on service. Not all service tasks are equal, and we can help our junior colleagues to assess the differences. If we see junior colleagues, especially women, being unfairly burdened with service responsibilities, we can help them find a way to let go of some or bring this to the attention of the appropriate department head or dean. Conversely, if we observe other colleagues shirking their fair share of service responsibilities, we can highlight the value and importance of service and promote the inclusion of service in performance evaluations.

If we have formal responsibilities for mentoring, serve on hiring or promotion committees, or hold a leadership position such as department chair or dean, then we can take steps to make more systemic changes. A simple but significant step is to increase transparency by honestly and openly conveying criteria for performance evaluations, including the service component. We can advise colleagues undergoing such evaluations about the expectations for current and future service activities. Of course, to do this effectively, we need to inform ourselves of the university expectations for service, realizing that these expectations have likely changed since we ourselves were junior faculty. We can improve accountability by working to ensure that service activities are tracked for all faculty colleagues, especially pre-tenure. With such information, we may be able to promote the fair distribution of service tasks and/or advocate for measures to offset service by overburdened faculty. One very relevant suggestion is not to ask for volunteers, since women are more likely to volunteer for service tasks than men [2]. Certainly, we should ensure that faculty job titles and salaries (or other compensation) reflect their actual responsibilities and duties.

With formal leadership positions (or even as individual faculty members), we can promote discussion and adoption of broader criteria for research assessment, such as those described in the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) [7] or the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA) [8]. A more flexible and personalized approach to defining professional career goals in academia has been developed – and is being applied – by universities in the Netherlands though the Recognition & Rewards Program [9]. A similarly broad, though less widely adopted program is the Better Science Initiative [10] described in a recent post [11].

It is clear that wide-ranging changes at the university level will only be possible with the support and engagement of the top university leadership (i.e., at the level of President, Chancellor, or Rector). Often rankings are used as the rationale to maintain conventional academic incentives. This minimizes the role of HERIs in perpetuating ranking systems. A re-examination of such systems and the constraints they place on the value that HERIs add to society is well overdue. Arguably, the ability of HERIs to address the complex challenges faced by society is not well served by the conventional academic incentive system [12]. Even the core task of educating students suffers from an over-emphasis on research productivity and international rankings. By undervaluing faculty service, HERIs – whether public or private – run the risk of a public backlash as well as maintaining barriers to the professional advancement of women faculty.

Questions for further consideration

· If you are currently employed as an academic, how much service work are you conducting compared with your colleagues, and how is the amount of service you are engaged in affecting your career in a positive or negative manner?

· Does your institution provide clear, frank, and transparent guidelines for faculty service expectations and are these guidelines followed in evaluation and promotion processes?

· How much mentoring did you receive over the course of your career on service opportunities and responsibilities, and how effective are you at mentoring others on the pros and cons of service activities?

References and notes

[1] Berenschot (2024) Recognition & Rewards Culture Barometer: First measurement report, 68463, https://recognitionrewards.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2024-Culture-barometer-Recognition-Rewards-first-report.pdf (Accessed January 5, 2026)

[2] Babcock, L., Peyser, B., Vesterlund, L. and Weingart, L.R. (2022) “Saying ‘no’ in science isn’t enough”, Nature Careers, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03677-6 (Accessed January 7, 2026).

[3] Macfarlane, B., and Burg, D. (2019) Women professors and the academic housework trap. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41 (3), 262-274. [not open access – a pdf can be requested from the authors through ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333942992_Women_professors_and_the_academic_housework_trap]

[4] Järvinen, M. and Mik-Meyer, N. (2024). Giving and receiving: Gendered service work in academia. Current Sociology, 73(3), 302-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921231224754 (Original work published 2025), [not open access – accepted author manuscript available at: https://research-api.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/100329934/j_rvinen_mik-meyer_giving_and_receiving_acceptedversion.pdf]

[5] Kvalsvik, G. (2024). “Women end up doing the academic housework”, kikinfo, https://kifinfo.no/en/2024/03/women-end-doing-academic-housework (Accessed May 2025).

[6] O’Meara, K.A., Kunaeva, A., Nyunt, G., Waugaman, C., and Jackson, R. (2017) “Asked more often: Gender differences in faculty workload in research universities and the work interactions that shape them”. American Educational Research Journal 54(6): 1154-1186 [not open access – preprint available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319127391_Asked_More_Often_Gender_Differences_in_Faculty_Workload_in_Research_Universities_and_the_Work_Interactions_That_Shape_Them]

[7] San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, https://sfdora.org/ (Accessed January 7, 2026).

[8] Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment, https://www.coara.org/ (Accessed January 7, 2026).

[9] Recognition & Rewards, https://recognitionrewards.nl/ (Accessed January 7, 2026).

[10] Better Science Initiative, https://betterscience.ch/en/#/ (Accessed January 7, 2026).

[11] https://www.epistimi.org/blog/better-science-initiative-sustainable-research-culture-for-all

[12] Urai, A.E. and Kelly, C. (2023) Point of View: Rethinking academia in a time of climate crisis, eLife 12:e84991, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.84991